“He was a huge difference-maker. He was a trailblazer. He cared about the community, and the community respected him.”

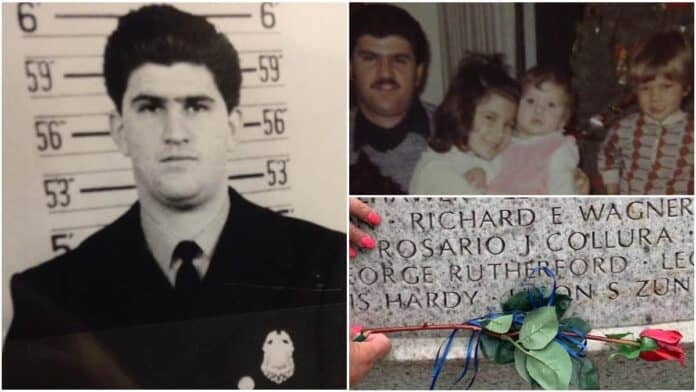

To the numerous African-American youths he mentored in the inner city, Milwaukee Police Officer Rosario Collura was a hero, a “difference-maker.” The officer they knew as “Rosie” regularly stopped by to check up on them, handed out baseball cards, and urged them to stay out of trouble. He was born and raised in district five, worked the district for almost 20 years, and died there, age 39. He cared about the kids, and they, in turn, cared about him.

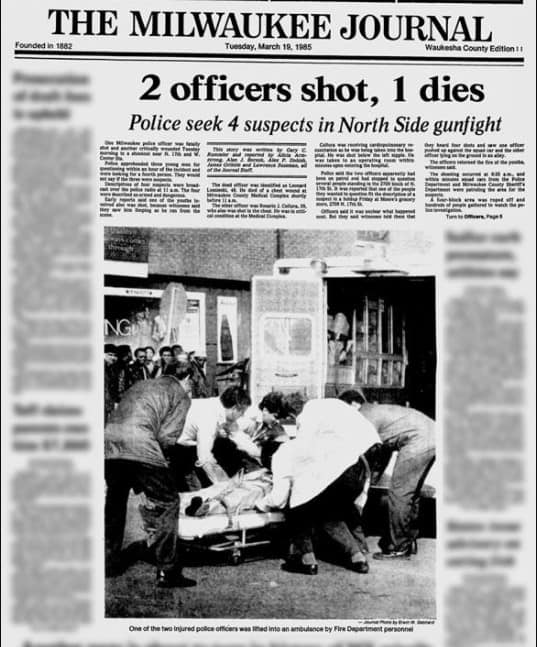

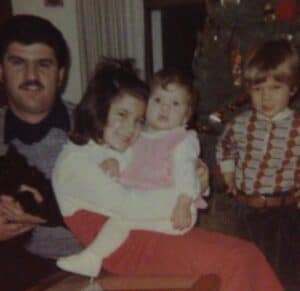

His daughter Helena Collura Ewer, who lost her father at age 12 when he was shot and killed with Officer Leonard Lesnieski while disrupting a drug deal on duty in 1985, learned the mentorship story years later from a Milwaukee firefighter who was one of those boys. The man met Ewer by chance on the job (she used to work at a jewelry store) 15 years ago, and he described how youths began crying when they heard an officer was shot and discovered that officer was Collura, a married father of three. She never learned the firefighter’s name, but we tracked it down for her: Marvin Coleman, now retired.

Coleman’s 1970s-era memories of the officer he called “Rosie” are just as powerful today. “Her father was a difference-maker,” he told Wisconsin Right Now. “He was a huge difference-maker. He was a trailblazer. He cared about the community, and the community respected him. He understood community policing way back when. Rosario Collura. Rosie. He was pretty much a vanguard to the neighborhood. Everybody respected him. He was a fixture on my (2nd Street) block.”

“He made such a difference,” Ewer told Wisconsin Right Now about her dad. “I heard so many stories. These officers make such a difference. He (Collura) was asked to transfer (out of his inner-city beat) multiple times, but he stayed. He said, ‘These kids need me,’ and he died there. He said, ‘I can’t abandon them.’”

Thus, it is with an awful and terrible irony that this brave officer’s family members, who have already sacrificed so much over the death of a man who quietly did so much for black lives, were made to endure a despicable display of abuse from Black Lives Matter protesters who descended on the Wisconsin Law Enforcement Memorial ceremony last week, which is held annually to honor fallen officers. Ewer and her brother, also named Rosario Collura, were chosen to present the wreath at the ceremony. Other family members of fallen officers were also subjected to verbal abuse at the ceremony, including children, who started to cry. Rosario Collura Jr. is now deputy police chief of a suburban Police Department.

A male BLM protester – who hasn’t been identified but whose image is captured on video – even walked up to Ewer while she made an etching of her father’s name on the monument. “Your dad deserved to die,” he told her. “He was a murderer.” She says he added, “I hope he suffered.”

She responded, saying what she should never have to explain: “You’re wrong; he was not a murderer. He was murdered. He spent 20 years trying to protect people so people like you can say these hateful things.”

When we told Coleman about this encounter, he was very upset. “We need police. Whoever did that should be ashamed of themselves,” he said. “I want people to know that his family didn’t deserve that. He was NOT a murderer. He was a helper. He was a hero to our neighborhood, you know, and we respected him as such.”

He added: “He (Collura) cared about us and the community at large. He absolutely made an impact on me. I never forgot him.” When Coleman heard Collura was murdered, he thought, “Why would somebody want to kill him? This guy cared about all of us.”

For years, when Coleman would go to the fire and police academy for training, he would always take time to stop by Collura’s picture. To remember the man who made such an impact in so short a time and then was suddenly gone. Perhaps the story of Rosario Collura and Marvin Coleman is symbolic of what we’ve lost in a sea of divisive rhetoric that dominates the media, and it’s what we need to get back to.

Protesters at the memorial flew an American flag marred with the words “f-ck 12” and played rap music that chanted “f-ck the police” over and over again during the memorial ceremony, which was attended by Gov. Tony Evers, Milwaukee Police Chief Alfonso Morales, and others. They even disrupted the opening prayer by yelling hateful things about police over a megaphone.

One woman, Sabrina Carpino, 35, of Madison, was arrested and Capitol Police are referring charges against her for disorderly conduct and disrupting a funeral or memorial service to the Dane County district attorney. The man who hurled the abusive comment at Ewer has not been arrested, even though he is captured on video hurling disrespectful comments during the service.

”I’m a pretty strong person, but I was shook; physically shaken. My husband held my hand,” Ewer told us.

After we ran a story on the BLM disruption and a separate story on the six officers whose names were added to the memorial this year, someone sent us a Facebook post that Ewer wrote about the experience. “Today was one of the hardest days in a long time…A piece of my heart was torn in two watching so many family members in such pain,” Ewer wrote. “As I sobbed through most of the memorial I could not help but think that my dad would want me to be strong.”

Moved, we contacted her to see if she would let us tell her story. She agreed, saying that officers’ families have remained silent for too long out of fear. She wants people to know the lasting pain that an officer’s on-duty death has on families, police, and the community. She wants people to remember the good works that so many officers do on a daily basis. She wants people to understand how warped the media narratives about police so often are (the media ignored the BLM disruption at the memorial).

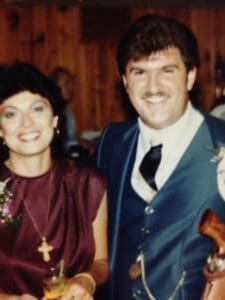

And mostly she wants people to remember her dad: The man who so loved gardening that he won a neighborhood beautification award, who ate chocolate ice cream with her from the same bowl when he came home from work, who married his high school sweetheart who withered down to 85 pounds after his death due to grief, and who could have transferred out of his inner-city beat after almost 20 years on the job but chose to stay because he didn’t want to leave the kids he was helping, including a kid who later became a firefighter and whose sister later became the first black officer on Milwaukee’s south side.

Officers Down

His death was the culmination of tragic coincidences. Two weeks before he was murdered, he had switched to the day shift. That morning for the first time in a long time, he didn’t wear his bulletproof vest. At that time, officers had to pay for their own vests; Ewer’s mother later donated money and pushed to have the city purchase vests as a part of officers’ uniforms. He was also covering someone else’s shift that morning, which was unusual.

Her dad was gunned down at “9:30 in the morning in an alley.” He was approaching an alley and didn’t even pull out a gun. Both Collura and his partner, Officer Leonard Lesniewski, were “shot point-blank in the chest.” Her dad knew the dangers of the job. He had been shot in 1973 but didn’t even take disability and went back on the job. He was stabbed once.

If her father had lived, Ewer wonders how many other youths he would have helped.

If he had lived another 20 years, she added, “How many more people could he have saved and mentored? When we hurt these officers and demonize them so badly they’re fleeing these roles, it’s your loss. It’s the community that suffers.”

If he had lived another 20 years, she added, “How many more people could he have saved and mentored? When we hurt these officers and demonize them so badly they’re fleeing these roles, it’s your loss. It’s the community that suffers.”

Coleman’s comments echo hers. “We all lost when he died. When his family lost him and the neighborhood lost him, it was just a terrible situation all around the board. Community policing is what needs to happen, and he was a leader before that was even a thing.”

Coleman, whose sister later became the first black officer on the city’s south side, doesn’t believe in defunding or abolishing the police. “No one does,” he said. “The crooks would love it. No, that’s not the answer. Maybe retraining.”

Ewer explained that her dad was on the job for almost 20 years. He worked the second and third shift at district 5, in the heart of Milwaukee’s inner city.

‘I Wish I Could Do More’

Rosario Collura was Italian, and the family was deeply embedded in the community. “My grandparents lived not far from there and provided meals all the time for the officers,” Ewer recalls. “They always had hot food on the stove for them at the time.”

She is the youngest of three, the most like her dad. “I’m a little more bold.”

Her mother married another Milwaukee police officer, but her grief altered the family dynamic forever.

“My dad liked to be the life of the party. He ran into the fire. He never waited for backup if someone was being hurt,” she said. “My dad dedicated 20 years in the inner city. He wanted to stay there and make a difference.”

But he saw the realities of crime and social ills. About a year before he died, she recalls standing at the top of the stairs and listening to her parents talk. Her dad said emotionally, “I wish I could do more, but I don’t know how to fix this. I can’t fix this. I don’t know what to do.” Some days he would come home and have to strip off his clothes because of the cockroaches and fleas he encountered on the job, she said.

But he saw the realities of crime and social ills. About a year before he died, she recalls standing at the top of the stairs and listening to her parents talk. Her dad said emotionally, “I wish I could do more, but I don’t know how to fix this. I can’t fix this. I don’t know what to do.” Some days he would come home and have to strip off his clothes because of the cockroaches and fleas he encountered on the job, she said.

“He said he couldn’t help the children. He was re-arresting the same people. They would beat up their girlfriend, the DA would drop charges, he would be called back to the scene to help. It would be the same reoccurring situation. People don’t understand what’s going on.”

She has watched with dismay as the public narratives harden in the media against police. “It was time to speak up and be a little more vocal,” she said. She started going to more memorials and helping other officers’ families.

She’s had more years to process the loss than others, but still it hits her very hard sometimes. The abuse at the memorial shook her. “It took me two days to calm down and relax,” she said. “It really hits me.” She also attended the Milwaukee memorial; that one was peaceful without protesters.

Ewer said she knows “Madison is a lot more liberal, but I just wasn’t expecting that. It was very difficult. I sobbed through the whole thing.”

She appreciated the words of Morales, describing him as an “incredible speaker.”

“I want people to see the reality for us, the loss and the pain and the grieving,” she said. “Everything in the news is about BLM and protesting.” She said fewer families showed up at the Milwaukee memorial, describing some officers’ families as being “scared. In hiding. It’s stressful for them.”

The protesters were so disruptive that you “could barely hear the memorial,” she said, describing them as “three agitators who were really close right on top of us” and about 15 people across the street. Supporters also were there, including children holding little flags.

“My husband said maybe this is the last time we are coming to Madison,” she said. “Chief Morales, you could see from the look on his face that he was devastated. These are fallen heroes.”

“It’s very frustrating for families to sit in silence,” she said. “You will never get it unless you’ve been an officer or a family for one. A half a second is life for them. No one else has a job like them.”

She said that fallen officers’ memorials are barely publicized these days because of fears that protesters will show up. “I know we have a ton of supporters out there,” she said. “But it feels like a lot of people have walked away.”

She said there have been anti-police movements in the past but “this is a whole other magnitude with cameras and video, and the media is only showing one narrative. The very liberal media will show a 10-second clip when there was 5 to 10 minutes leading up it.” She knows officers who have been followed home after their shifts or received harassing letters in their mailboxes. Sometimes she calls them at night just to tell them, “I’m here for you.”

‘Daddy’s Little Girl’

Ewer was the youngest of Collura’s three kids. “I was daddy’s little girl,” she said.

“When he got home at 1 or 2 in the morning, I would wake up and come down and see he was home, and he would get out chocolate ice cream and get two spoons, and we would eat ice cream from the same bowl, and then I would go to bed.”

“When he got home at 1 or 2 in the morning, I would wake up and come down and see he was home, and he would get out chocolate ice cream and get two spoons, and we would eat ice cream from the same bowl, and then I would go to bed.”

She said he coped with the stresses of his job by gardening. He was “always bent over gardening before he went to work,” she said, remembering all of the fruit trees he cared for.

Collura said she isn’t surprised the media “didn’t cover the situation accurately,” referring to the memorial. “We are quite a divided community right now, but our media goes one direction. It’s hard to find reporters who will legitimately show both sides.”

She recently got a tattoo in honor of her dad. The grief never goes away. “My brother was my protector,” she says, describing how they “tried to make our family as normal as possible afterwards, but it was really tough. My dad was the center of all the family gatherings, and he would invite all the cops over. When he was gone, everything stopped. It was a really rough couple years.”

Her mother turned to the church, but she had to force her to eat a cheeseburger when she withered away to 85 pounds, telling her, “If you die, then I don’t have anyone else.” She said the officers’ killer won’t ever get out because he later assaulted two correctional officers with a hammer in prison after being given a prison job working in a furniture-making facility.

Her mother turned to the church, but she had to force her to eat a cheeseburger when she withered away to 85 pounds, telling her, “If you die, then I don’t have anyone else.” She said the officers’ killer won’t ever get out because he later assaulted two correctional officers with a hammer in prison after being given a prison job working in a furniture-making facility.

The killer later said “he did it because he did not want to go back to jail,” according to a Milwaukee police memorial page.

“Officer Collura and Officer Lesniewski interrupted a drug deal at N. 17th Street and W. Center Street. The officers began frisking the men. As one of the men was searched, he pulled a gun and shot both officers in the chest,” the page says. “Officer Lesniewski died from a bullet to his heart. Officer Collura made it to the hospital and was expected to survive but died about six hours later from uncontrollable bleeding.”

The page adds: “Officer Lesniewski was 48 years old and became an officer in March 1969. He moved to the 5th District in April 1984 after 15 years in District 4 on the Northwest Side. He served fours years in the Marine Corps and married his wife Carol when they were 23. They had two daughters.”

Ewer said that people don’t understand the loss and PTSD faced by the officers who remain.

“They are human beings doing a job.”

It’s a simple wish from someone who has already endured too much: Always remember. Never forget.

Coleman is one person who never will forget the officer who took the time to stop his squad and talk to a little boy with big dreams of becoming a firefighter someday. Years later, when he would take out the rig, he always made sure to stop and talk to the kids, thinking of Collura’s example.

“People need to learn about each other and be willing to help each other,” he says.

Collura was someone who understood this, who lived it out. “He understood community policing before that was even a term,” Coleman said. “We need more of them. We need more guys like him.”