What are the lessons of 9/11? Our nation’s first responders do not deserve to be falsely turned into villains; they are heroes. We need to unify our country, its people, and its security. Patriotism is a beautiful thing; love of country is too. We should celebrate our country’s ideals and defend them. And we have to take the fight to terrorists elsewhere so it doesn’t revisit our shores.

In the days after Sept. 11, 2001, I spent the night in a New York firehouse right around the corner from Ground Zero, watching as the heroic and traumatized first responders trudged back and forth to dig on the massive pile, finding nothing but dust and dirt and rocks, sometimes clawing at it with their bare hands, and returning with their faces streaked with grief and determination before going back out to dig yet again. What else could they do after all, they told me; they were spared. These men were salt of the earth; the best America’s got.

Yet even as they dug without sleeping for days, they paused to care for strangers, even as strangers came to the firehouse near Ground Zero to care for them, bringing too much food, boots, and flowers for anyone to ever use. Everyone was briefly unified in America then, everyone was patriotic (people were walking around draped in American flags and hardened New York cabbies were giving people rides for free), and everyone in the country seemed to agree that our nation’s first responders (cops and firefighters like these) were heroes. They were the people who ran toward danger when everyone else ran away from it, the saying went.

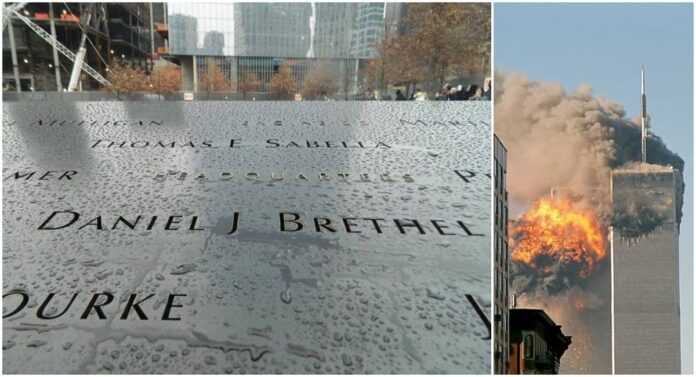

Never forget. Remember this photo of the 9/11 memorial at Ground Zero. It will have great significance by the end of this article.

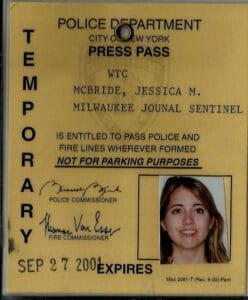

I was sent to New York on Sept. 11, 2001, as a journalist, by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The editor said, “Get in a car and go,” and I did. About 100 miles out, we started to see electronic signs saying New York was “closed.” It was almost impossible to get into the city, but we found a train that went there. We were accompanied on the almost empty roadways by the rescue workers from all over the country coming to volunteer. I arrived with a photographer in Manhattan on the morning of Sept. 12, 2001, and I spent the next two weeks there. It changed me forever; this is when I developed a respect for the role of law enforcement that has never left me.

A couple of years ago, while teaching a journalism class at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, I realized that Sept. 11, 2001, was no longer a living memory to my students. It happened gradually. First, they remembered it, but only through the emotions of adults – a frantic teacher, an upset parent. Some were affected by it, all the same; some students had parents who went to war, for example.

Now, my students have no living memory of 9/11 at all in most cases. They were infants, if alive at all. To them, 9/11 is dispassionate history, like the Kennedy assassination is to me.

My father has an emotional response to the assassination to this day because he lived through it. I didn’t, so, to me, I don’t feel the tragedy, although it interests me. It’s worth pondering what that means and what it changes. I think it matters because, if you don’t feel a tragedy, you may be more likely to forget its lessons, and I’m speaking of the country overall now.

Back then, we would never have tolerated such a haphazard and chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan for example. We would never have been okay with leaving Americans behind or ceding a country to the terrorist group that harbored Bin Laden. That’s because we lived it. We FELT the tragedy. We mourned the deaths.

It’s incumbent on those of us who were there and who lived it, even if from afar, to be the curators of that history and the voices of it. They say journalism is the rough draft of history; never is this more true.

The Lessons of 9/11

What are the lessons of 9/11? Our nation’s first responders do not deserve to be falsely turned into villains. They are public servants who deserve our respect, and who put their lives on the line for all of us, the dividing line between order and disorder, life and death.

We need to unify our country, its people, and its security. Patriotism is a beautiful thing; love of country is too. We should celebrate our country’s ideals and defend them. America is a great, albeit sometimes imperfect country, and it is our home. And we have to take the fight to terrorists elsewhere so it doesn’t revisit our shores (but do it strategically and smartly).

Take care of and honor our veterans and never forget any of our dead, including those who fought the wars that came. And, yes, remember why we went to Afghanistan as part of that. The architect of 9/11 was being harbored there. We were right to go there. It was not right how we left.

How soon some forget.

Never forget.

I remember shards of memories…. the Korean grocer, his fruit blanketed with the dust of the dead a few blocks from Ground Zero, letting firefighters take whatever they wanted off his shelves…

The firefighter who was so traumatized he drove through red lights without realizing he was doing it…

How salt of the earth they were, how much grief they endured…

The dust that chapped our lips and dried our throats and smelled like burnt wire (it’s the only other time I wore a mask before COVID, but it wasn’t a very good one)… it was a crematorium really…

The parades of construction workers, police and firefighters from all around the country, coming to dig, with little American flags tucked into their helmets, trudging through the damaged streets…

The citizens walking around with American flags draped over their shoulders or hanging them from apartment windows…

The way a couple pieces of metal at Ground Zero naturally formed the shape of a cross, which became a symbol for the rescue workers…

How they had to bury live people now and then so the rescue dogs wouldn’t look depressed because they weren’t finding anyone alive…

The story about the fire department’s chaplain being killed by a jumper and being carried to the altar of St. Peter’s Catholic Church…

I remember the burnt shells of police cars, overturned on the streets, the fighter planes zooming past overhead, the Red Cross workers handing us bottles of water, the inability to get a cell signal because the towers were on the Trade Centers…

The endless sirens and emergency vehicles…

The photos of the people who decided jumping was the better option… and the awful sounds of their crashing falls on video… the dust, always the dust.

I remember when the missing posters started turning up, cries of hope pasted to subway station walls and random buildings, faces and names. They were pictures of husbands and wives and traders and waiters and sons and daughters, people who would never, ever get to come home, but people didn’t know that for sure yet then.

For the most part, there was only dust, bits of shredded paper fluttering around, and shoes that people had run out off. And a few bodies or parts of bodies, but not many. Human lives obliterated by those threatened by the cause of freedom.

Never forget.

In a story I wrote for the Journal Sentinel, in one of many dispatches from the blocks around Ground Zero, I penned this series of paragraphs high up in the story about the firefighters going back and forth to dig. A broadcast of the number 5 came over their radio. I wrote:

For as long as anyone can remember, those numbers have meant one thing to a firefighter in New York: One of their own has fallen. Although few remember why, the tradition originated in the days when bells were used to impart the message; they were rung five times.

A few minutes later, the expected announcement. The only mystery is which firefighter – or piece of him – has been pulled out of the mountain of rubble this time:

‘It is with regret that the department announces the death of Captain Daniel J. Brethel of Ladder Company 24, which occurred on September 11, 2001, as a result of injuries sustained while operating at BOX 55-8087.’

Box 55-8087 is the department’s code for the original disaster call.

Years later, I took my young daughter, Annie, back to Ground Zero, to the memorial.

In 2001, I had arrived there the morning after the terrorist attacks, driving to New York, and the first thing that came to mind was that the landscape resembled a nuclear holocaust. For days, I breathed the dust of the dead. People were literally erased, their early remains tossed into the air around us.

Now, years later, in 2019, there was a sterile shopping mall on the site, and a memorial wall of names with a fountain-type memorial. It was a jarring contrast between reality and memory, and not a particularly good one. I looked at the tourists parading around the memorial, standing before the names, and I wondered if any of them really knew what it was like there, then. How much trauma was harbored in that spot. How much grief, and loss. How it was also the spot of love and devotion and dedication from those who came to dig.

Annie and I paused at the memorial. I didn’t focus on any name in particular. My photos show other names.

But she was randomly snapping photos as it began to rain. She was 13 years old. Later, when I got home and went through her random pictures, I noticed that she had focused on one name, without ever having read my story and without ever knowing why or what it meant.

Daniel Brethel

Daniel Brethel was that name. She had stopped for some reason before that name and trained her camera lens upon it. I didn’t even realize it until later.

Daniel Brethel was 43 when he died. “Danny was born a fireman,” says a tribute to him on the National Fallen Firefighters Association page. “This was all he ever wanted to be and he always said he was living his dream. He was very dedicated and loved his job and those he worked with. Danny was even more dedicated to his family. There was nothing he wouldn’t do for his girls‚ Kristin and Meghan. He was so proud of their accomplishments. One of Danny’s greatest joys was taking his family out on his boat for a day of swimming and exploring. Danny lived his life to the fullest. He was the heart and soul of our family and we miss him terribly. ”

There are so many names, but Daniel Brethel stands as a symbol of the first responder tradition and of my earlier point: Cops and firefighters, our first responders, are heroes.

When I looked at the picture Annie took, and saw that name, I had goosebumps.

A raindrop formed what looked like a tear in Annie’s photo beneath his name.

Never forget.